范昆仑:Credit Derivatives, Emerging Markets, and China

范昆仑 Colin Fan/Managing

Director of Deutsche Bank (in England)

In the fixed income world, there are three fundamental market risks: interest rates, foreign exchange, and credit risk. The financial instruments used to manage these three types of risk are continually improving, especially since the development of financial derivatives, which separate the risks from the underlying instruments. Futures, forwards, swaps, and options are all attempts to isolate specific characteristics of cashflows in order to better control the size and nature of the risks.

In interest rates and foreign exchange markets, the derivatives available have become extremely sophisticated, with some instruments that border on fantasy. Markets are also very efficient -- prices in bonds, swaps, and options are consistent. Ironically, credit markets are still inefficient. A bond, loan, promissory note, letter of guarantee, or any other recourse instruments has credit risk embedded. However, the same credit risk does not carry the same price in the separate credit markets: the difference between two instruments with the same credit risk and same maturity can be many percent in yield. Most of this difference exists because of the limitations in "shorting" or selling credit risk. Consider a loan or promissory note of a certain bank. If the price of this asset is very different from a bond of the same maturity, there is no way to arbitrage this difference and remove the inefficiency in the market.

Credit derivatives solves this problem by making credit risk fungible. Buying and selling credit risk synthetically through default swaps facilitates credit risk transfer from hedger to investor, which increases the overall liquidity and efficiency of the market. As a result, credit risk has become an explicit parameter in risky portfolios that can be managed dynamically instead of statically. The incredible increase in the use of credit derivatives demonstrates the appeal of the product and outpaces the growth of any derivatives market.

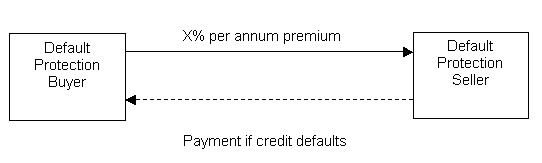

Credit derivatives is defined as

the set of derivative products with credit as the underlying risk. The basic

building block of credit derivatives is the default swap, which is simply an

insurance policy on the risk of default by the underlying credit.

For example, for Bank of China credit risk with 5 year maturity, the default swap premium is 1.00% per annum. On USD 10 million notional, this means the default protection will cost USD 100,000 per year in premium. If Bank of China defaults, the Protection Seller will pay the Protection Buyer USD 10 million and receive the defaulted assets in exchange.

The pricing for this simple instrument ranges from simple cashflow discounting to complex stochastic models. One simple way to conceptualize the pricing is by the following formula:

NPV = Cashflow*Risk-free Discount

Factor*(1-P)

Where NPV is the net present value

Cashflow is the cash payment being valued

Risk-free Discount Factor is derived from the risk free interest rate

P is the probability to default to the maturity of the cashflow

In this generalized equation, P is the unobservable variable that is the challenge in quantifying for all pricing methodologies. However, at a minimum, whatever method of deducing P is used, the above formula produces internally consistent pricing for any set of cashflows with the same credit risk.

So, for the example of Bank of China, a set of cashflows, whether bonds or loans or even contingent payments (e.g. options) can be priced fairly against the probability of default of the Bank of China. Furthermore, any discrepancies can be arbitraged out of the market to increase efficiency and liquidity for this underlying credit.

Default swaps are the basic building blocks of more complex credit derivatives products. Credit Linked Notes, First-to-Default baskets, synthetic portfolios, and hybrid credit / interest rates / equities / commodities swaps are only a few examples. In fact, any payment contingent on credit risk can be classified as a credit derivative, and the principal underlying such an instrument is the same as the default swap mentioned above.

The uses of credit derivatives are varied and broad, but can be sorted into the following categories:

User:

Purpose:

Banks: for hedging loan portfolios and other credit products

Insurance: for investing premiums to match long dated

Real Money Accounts: for fixed income investment

Corporates: for hedging receivables and credit facilities

Hedge

Funds: for speculation

Of course, credit derivatives technology applies to any underlying credit risk, from countries to companies and investment grade to high yield debt. There are small differences in detail between the markets but the same overall contract applies to all credits.

Deutsche is the global leader in developing and dealing in credit derivatives. By all measures of market share, innovation, and customer feedback, we have and continue to drive this market. At Deutsche Bank, I specialize in trading all credit derivatives (countries and companies) related to emerging markets debt.

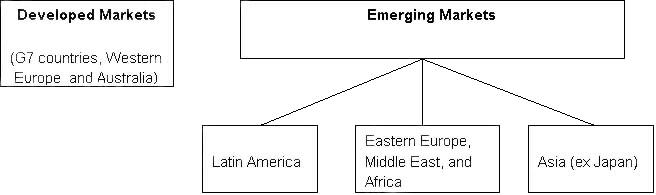

Emerging markets is usually defined as a market that is still developing to the standards of the major capital markets such as U.S., Western Europe, and Japan. Many factors such as liquidity, transparency, fairness, regulation, government stability, size of the economy, and per capita income define which markets are considered emerging markets. However, a precise classification is difficult since many variables are dynamic and subjective. In international credit markets, the conventional classification is that any country outside of the G7, Western Europe, and Australia are considered emerging markets. By this convention, China is considered an emerging market. However, it is a special case since it is viewed as a country that not only has the greatest potential to emerge into the developed markets, but also to catapult into the forefront of the developed markets.

Within emerging markets, there are

3 broad regions:

International investors view the emerging markets as a riskier area to invest, and typically demand higher returns to justify the investment. As a result, the interest rate that emerging markets borrowers pay tends to be higher than a comparable borrower in the developed markets.

This risk aversion is based upon history as well as logic. Present history of emerging market debt starts in early 1980s after Nicolas Brady, former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, helped to restructure the commercial bank loans of various countries into securitized bonds, which provided relief to the debtors and tradable bonds for emerging markets investors. Since then, emerging markets bond investors have suffered crisis after crisis set off by various catalysts: Mexico's devaluation in 1994, Thailand 's devaluation in 1997, Russia 's devaluation in 1998, Brazil 's devaluation in 1999, and Argentina 's devaluation in 2001. In each case, emerging markets as a whole was punished for the disturbance in one country. This "contagion" effect is the unfortunate consequence of being classified as an emerging market during crises. Worldwide economies, not just financial markets, suffered the consequences. In fact, it is not unfair to say that the solution to each crisis may have contributed to the seed of the next crisis.

Two important conclusions can be drawn from these experiences. First, credit derivatives are a necessary and beneficial tool for any participant in the emerging markets. Second, China 's emergence out of the emerging markets category is not only for pride and honor, but also necessary to avoid the same fate either directly through the same mistakes or indirectly through contagion.

First, on credit derivatives, the obvious use is the efficient transfer of credit risk from the hedger to the investor. This can be done on a single name basis (like the Bank of China example above) or entire portfolios (for example, a portfolio of loans that the Bank of China owns). Buyers of the risk can price credit risks that they do not have access to. Sellers of the risk can quantify the value of their portfolios and sell the risk in a highly customized fashion. As an example, imagine that Bank of China has a portfolio of 200 loans to companies with various loan agreements, some of which are confidential. Bank of China is happy with the credit quality of the portfolio for the next two years but not as certain after that. Bank of China can sell this portfolio today through a default swap that begins in two years on all 200 company names, without revealing any of the original loan documents. This way, Bank of China can discover the value of the loans on its books at any time, eliminate the credit risk at the time it chooses, and still hold all the loans on its books. Of course, this is the simplest example since credit derivatives can be customized into anything the buyer and seller agree to, so the terms and conditions are flexible enough to accommodate any variation.

Second, on the development of China's financial system, credit risk is of primary concern. International investors are well aware of China's vast potential as the next financial superpower. The population, natural resources, and geopolitical environment are all advantages to propel China out of the emerging markets category. However, there are still some perceived weaknesses that China shares with the emerging markets. One of the most important is non-performing loans and the credit deterioration in the financial system. It is well known that China has supported many state enterprises and that the state banks carry the heavy burden of the credit risks. Some outside experts estimate that China's public debt could be six times higher than the official figure of 23% of GDP if this burden were included. If and when China decides to completely open its financial markets to the international capital markets, the systemic credit risk will be scrutinized. In most emerging markets cases, the eventual failure has been traced to the markets' reaction to discovering the amount and concentration of credit risk in that system.

Credit risk is one of the most difficult risks to capture and control because it is invisible. Stock prices, exchange rates, and interest rates fluctuate across millions of screens daily and are accessed around the world for buying and selling those risks. Credit is only partially represented by the bond prices that trade globally. The majority of credit risk is invisible and locked up in the loans, guarantees, and bilateral obligations that cannot be easily assigned a price or even transferred. Even in the most developed markets, such as the U.S., credit risk has been a challenge to manage. Only now, with the development of credit derivatives, can credit risk be as easily traded as stocks, foreign exchange, and interest rate risks. Hopefully, this will help institutions to better manage one of their most basic risks. China can be a prime beneficiary of this new product as China leaps out of the emerging markets towards the front of the developed markets.